The Complaint

George is fed up with the delayed rubbish collection and pens a withering complaint to the council, but his attempt to deliver it takes a dark turn.

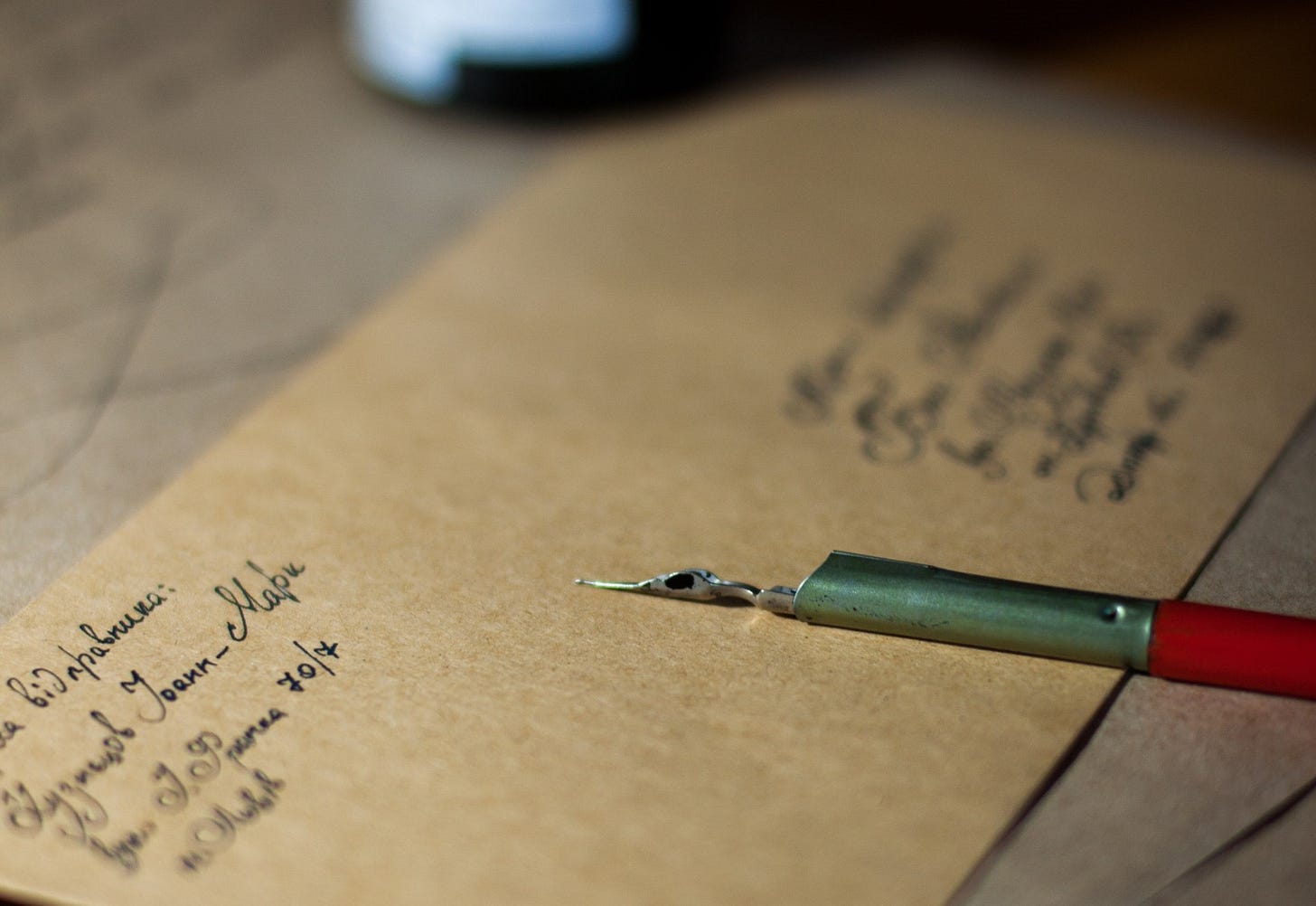

George McDonald took the tip of his pen lid out of his mouth and wrote the first line of his complaint.

‘To whom it may concern.’

He paused, considered whether it ought to be addressed to the leader of the council, then decided against. He continued:

‘It has now been 102 days since my bins were last collected. In that time, I have written twenty-four formal written letters of complaint. Imagine my dismay to not have received a response of any kind!’

The Parker pen felt heavy and familiar in his hand: a gift from the office on his retirement. What a wonderful day that had been, he thought, smiling fondly, an occasion surrounded by friends and rivals alike, all smiling, all pleased to share with him this rite of passage. He was even able to forgive the misspelling on the engraving: ‘Happy retirement, George MacDonald’.

The tick of the clock went on, in stately certainty, as the heavy paper waited patiently for him to finish his musing. He ran his finger over his pen’s well-worn engraving and resumed his letter.

‘As you are well aware, the local authority possesses a legal duty under the Environmental Protection Act 1990 to collect household waste to prevent a hygiene hazard. Given the current situation, you will be unsurprised to learn that the council has been highly negligent in this regard. In fact, it appears to be actively trying to kill its residents.’

This paragraph, George felt, was an improvement on the first, since it contained both a reference to legal duties and negligence. This was very pleasing to George. He had long since learned that it was important to appreciate the small things, such as the stroke of a thoughtful pen, or a well-placed word. Completing the cryptic crossword, for example, was a favourite ritual, completed in total silence with tea and a bourbon.

His stomach growled. He went on.

‘I request demand that the council recognises its obligations to its residents by clearing away the vile filth clogging up our pavement by next week, Otherwise, I shall be forced to consider legal action.’

He studied the crossing out; would it ruin the effect? No, he decided, now reduced to munching on the metal end of his pen to appease the growing hunger. It would only demonstrate the strength of feeling.

The pen flew across the page, then paused. He could not decide how to sign off. Eventually, he plumped for simplicity:

‘Yours Faithfully, George McDonald of 32 Therapia Gardens, Chiswick.’

Letter complete, George took the well-earned opportunity to push back his chair and survey his handiwork. Not bad, he felt, not bad at all, and certainly firm enough to do the job. It should ruffle a few council feathers at any rate.

He inspected the letter one last time, before folding it into three with a crisp, straight fold and placing it in the empty envelope he had left to one side, the last of his supply. He wrote the familiar address in black capital letters to avoid any short-sighted underling misreading the handwriting and leaving it on the wrong desk.

Now for a stamp, he thought.

He opened the desk drawer, which glided open because he’d oiled it last week. This was a bit of an extravagance, times being what they were, but he could not bear a squeaky drawer.

The drawer seemed empty. He scrambled around at the back, his fingers seeking what ought to be there, but he found nothing. The scrambling hurt his fingers, which were already weak and shaking from all the careful writing.

‘Damn and blast. Hells bells, and buckets of blood,’ he said out loud to the closed brown curtains, which were always closed now. His mother would have been shocked to hear him say such words, but then his mother was not here to hear, God rest her dried up excuse for a soul.

Banishing his mother back to her cold, hypocrites heaven, George inspected the remaining drawer for stamps. But there were only old newspapers with completed crosswords, damn it.

The drawer shut too hard and knocked the pen jar off, scattering several blunt pencils all over the floor. He wanted to cry. All that hard work writing his letter, and for what? He crouched down, a slow, jerking movement that must be measured inch by painful inch, and fumbled for the pens. He could hardly see anything in the fading lamp light. He ought to write to the electricity company; the power was so unreliable. Where were his glasses, again? On the desk, no doubt.

His scrambling hands reached out and found a tiny scrap of paper. He stroked it, feeling its smooth surface, picked it up between thumb and forefinger and brought it shakily to his nose. It was an unused, first-class Royal Mail stamp.

He could have leapt with joy, but his back protested too much, so he eased up gently and kissed the stamp instead. Then he licked the back and placed it with a flourish on the envelope. A little dramatic perhaps, it only being a stamp, but the drama was earned.

Finally stamped, the letter lay there, complete and waiting to be posted. Yet George hesitated. Could he send such a letter? Was it too demanding? Could it be seen as aggressive? Perhaps, he considered, but consoled himself with the thought that had been treated unreasonably. He was right to complain.

He took the letter and went to the porch. He put on the heavy, outdoor boots, then the insulated reflective overcoat and the rubber gloves. His skin snarled with pain as he dragged the gloves over his arthritic hands, but he gritted his teeth and tolerated it. Then he lifted the suit from the hook. It was a full orange body suit, covering coat, gloves, boots and all, and went up to the neck. Last came the helmet, with its dark protective grille, which he screwed on tight to avoid any air pockets. Several months before he’d been careless and ended up with… well, it was best not to dwell on that. He was better now, mostly.

Walking like an automaton in his heavy ridiculous clothing, George took a deep breath, picked up the letter in rubber fingers then keyed in the lock code with his free hand.

The shrill beep went five times, and a voice said, ‘Are you sure you wish to exit?’

Yes, yes, yes, damn it! He punched in the code again.

The alarm continued for a minute, but then the door relented, and he was able to push it open.

A blast of freezing air hit him first. Then came the sick, heavy feeling that seemed to emerge from your bones and push outwards, his body intent on melting from within. Everything felt weak, like being suddenly hit by flu. He gritted his teeth, thought of England, and went on.

Thick darkness surrounded George McDonald as he made his way to the end of his garden, or what had once been his garden, for everything in it was dead. Geraniums, grass, marigolds, dandelions, all turned to black soup. Only the stone path remained, which he could not see. It was 10.30am, according to the indoor clock, but out here was eternal midnight, or beyond midnight, some kind of post-time scenario where there is only black. The tiny flashlight on the top of his helmet made a weedy attempt to create light, but it might as well have been broken. He walked to where he thought the gate was and almost collided with it. It swung open with a loud and terrible shriek in the silence of what was once Therapia Gardens.

George fumbled in the suit’s pocket and pulled out the larger torch. He swung it around and the postbox flashed like a red beacon in the dark. It was ten feet away, but it took George at least ten minutes to reach it, having to stop after every step as the radiation pushed its way through his protective clothing like fire through paper. Best available protection, they said, preventing seizures and instant death.

At last, George could see the postbox in front of him, a red monster with a smiling black mouth. His vision began to swirl, and with the last of his strength he reached up and pushed the letter through the slot.

It fell with a papery flop.

Letter posted, George took a breath, but not too deep, to avoid breathing too much contaminated air. He’d made that mistake before; the vomiting lasted days and days, and he even now he sometimes coughed up dark blood, resembling tar.

Get back inside, now.

He walked fast as he could, which was not nearly fast enough, heading back through the gate and down the path. Nearly there, George, he told himself, nearly there. He reached the door and pressed his hand against the panel.

The door made a hissing sound. He leaned up against it, strength gone. Please, he thought desperately, open up. He feared that one day it would not and he would be left on the wrong side, melting in silence with not one soul to hear his screaming.

Don’t be morbid, he told himself, as the door opened. What did mother always say? Worse things happen at sea.

He staggered indoors and the door closed automatically behind him.

‘Wait thirty minutes for decontamination,’ sung the chirpy voice inside the door, and powder poured down on his suit. George shut his eyes. Slowly, so slowly, the burning in his bones began to subside, until it was only a warm hum. The process was supposed to be 30 minutes in total but felt longer each time he went out.

After far too long, his front door opened and he saw his welcoming hallway again. He ripped off the suit as fast his shaking hands could manage, then staggered onto the ‘Home Sweet Home’ mat, his feet still white with the powder. He’d hoover it all up later. Now he just needed to sit down and have a tea, and a bourbon.

Of course, there was no tea. That went last month. The bourbons went long before. There were the crackers, of course, but he should save those. In the past he was reckless with food but it too late to regret that. Regretting changed nothing.

Still. He could have a sip of water. That wasn’t completely on ration yet.

He fetched a water bottle from the larder, then went to the calendar and circled the date of next Tuesday. He’d wait until then for a reply from the council. Then he’d write to a lawyer. He had a list of local firms somewhere, if he could find it.

Tasks done for the day, George perched in the easy chair with his water bottle and looked at the black screen of the long dead TV. Lot of rubbish anyway. Not worth watching even when it was on.

He decided to do a crossword instead. Goodness knows, he’d earned it.

He got up, wincing with the pain and shuffled over to the desk. He opened the old newspaper drawer and took one out at random, then picked up a stray pencil from the floor and shuffled back to his easy chair. This done, George turned the yellowing paper over to the crossword section, averting his eyes from the headlines. All grim stuff, not worth dwelling on. Still without looking, he used the grey rubber at the end of the pencil to wipe out all the crossword answers.

Satisfied, George looked down at the now blank puzzle. Most of the squares were grey smudges, but it didn’t matter, since the pencil was so blunt. What mattered was the mental act, the discovery and writing of words onto paper.

George chewed the end of his pencil, considering the first clue. Above him, the grimy light bulb flickered, then went out. When it would come back, he could not say. Maybe never.

He sighed. No crossword for him today. Never mind. Worse things happen at sea, as they say. As they used to say.

George McDonald sat alone in the darkness of his living room and listened to the steady tick of the clock.

I loved this. It read like a novelisation of Keeping Up (Post Apocalyptic) Appearances. I felt that it conveyed a powerful message about the importance of maintaining structure, routine and the human connection of communication (albeit unanswered).

This is great. I love that he seems to not care (or hasn't processed?) that there are no people left to complain to. I bet that post box is chock full of his letters to the council. I thought he was turning into a zombie, but I suppose radiation sickness is just about the same thing.